Initial Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock in Adults

Initial Resuscitation of Adults with Sepsis and Septic Shock

Last Full Review: Surviving Sepsis Campaign 2021

Sepsis is a significant healthcare problem accounting for an estimated 6 percent of hospitalizations in adults and resulting in a considerable economic burden (Paoli et al. 2018, 1889). Mortality varies with severity from 5.6 percent to as high as 34 percent for septic shock. The early recognition and management of sepsis is key to improved outcomes. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) is an international collaboration committed to reducing the mortality and morbidity associated with sepsis and septic shock through evidence-based guidelines, best practice statements and recommendations for treatment. Updated adult sepsis guidelines were published in October 2021 by the SSC (Evans et al. 2021, 1). Guidelines for the care of pediatric sepsis and septic shock were published by the SSC in 2020 (Weiss et al. 2020, e52). The Red Cross guidelines for the initial management of adult and pediatric sepsis and septic shock are informed by the SSC guidelines.

Red Cross Guidelines

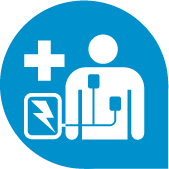

- Adult patients with sepsis and septic shock should be treated immediately and resuscitated, to include:

- Administering at least 30 milliliters per kilogram of intravenous crystalloid fluid within the first 3 hours of resuscitation of patients with sepsis-induced hypoperfusion or septic shock.

- Using dynamic parameters, such as response to passive leg raise or fluid bolus, stroke volume variation or pulse pressure variation over static parameters or physical examination alone to guide fluid resuscitation.

- Using capillary refill time as an adjunct to other measures of perfusion to help guide resuscitation. Use of capillary refill time to guide resuscitation should be accompanied by frequent and repeated comprehensive patient evaluation to predict or improve early recognition of fluid overload.

- Using a decrease in serum lactate to help guide fluid resuscitation of patients with an elevated lactate level.

- Using an initial target mean arterial pressure of 65 millimeters of mercury for septic shock requiring vasopressors.

Evidence Summary

A review of the evidence was completed by the SSC on topics related to the initial resuscitation of a patient with sepsis or septic shock, to include the choice and volume of intravenous (IV) fluids, use of dynamic measures to assess fluid responsiveness, use of capillary refill to assess tissue perfusion and initial resuscitation targets for mean arterial pressure (MAP) (Evans et al. 2021, 1).

The recommended minimum volume of IV crystalloids for initial fluid resuscitation is based on observational studies, with one retrospective study (Kuttab et al. 2019, 1582) of adults with sepsis or septic shock in an emergency department setting showing an association between failure to receive 30 milliliters per kilogram (ml/kg) of crystalloid fluids within 3 hours of sepsis onset and an increased length of intensive care unit (ICU) stay.

An association between an elevated serum lactate level and the likelihood of sepsis is established and part of the definition of septic shock (Shankar-Hari 2016, 775). Other studies have evaluated the use of lactate as a means of screening for sepsis in adults with clinically suspected sepsis (Contenti et al. 2015, 167; Ljungström et al. 2017, e0181704; Morris et al. 2017, e859). However, the SSC notes that a serum lactate level alone is neither sensitive nor specific enough for diagnosing sepsis and should be interpreted based on the clinical context and with consideration for other causes of an elevated lactate level. For these reasons, a weak recommendation is made for the measurement of serum lactate levels in adults suspected of having sepsis (Evans et al. 2021, 1).

Beyond the initial 30 ml/kg initial fluid resuscitation, dynamic measures, such as response to passive leg raising combined with cardiac output measurement, and response to fluid challenges with stroke volume, stroke volume variation, pulse pressure variation or echocardiography can be used to predict fluid responsiveness as compared with static measures such as heart rate, central venous pressure and systolic blood pressure. A systematic review with meta-analysis showed that the use of dynamic assessment to guide fluid therapy was associated with reduced mortality (RR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.42–0.83), intensive care unit length of stay, and duration of mechanical ventilation (Fleischmann-Struzek 2020, 1552). In settings with limited resources, fluid responsiveness can be predicted by a greater than 15 percent increase in pulse pressure with passive leg raise testing (Misango et al. 2019, 151).

Capillary refill time has been shown to reflect tissue perfusion (Cecconi et al. 2019, 21; Lara et al. 2017, e0188548). When a normal capillary refill time target is used as a resuscitation strategy, it has been found to be more effective than a strategy targeting normalized or 20 percent reduction of lactate in the first 8 hours of septic shock (Hernández et al. 2019, 654). The SSC cautions, however, that an approach using capillary refill time to guide fluid resuscitation should be augmented by repeated and comprehensive patient evaluation to predict or promote early recognition of fluid overload (Evans et al. 2021, 1).

The recommendation for an initial target MAP of 65 millimeters of mercury (mmHg) is unchanged from previous SSC guidelines and reflects evidence from a randomized controlled trial (RCT) that showed no difference in mortality between patients given vasopressors with a target MAP of 65 mmHg to 70 mmHg compared with a target MAP of 80 mmHg to 85 mmHg but showed a higher risk of atrial fibrillation in the high target MAP group (Hylands et al. 2017, 703).

A more recent RCT (Lamontagne et al. 2016, 542; Lamontagne et al. 2020, 938) compared permissive hypotension (mean arterial pressure, 66.7 mmHg) with “usual care” with vasopressors and an MAP target set by the treating physician (mean arterial pressure, 72.6 mmHg) in septic shock patients aged 65 years and older. The intervention group had significantly less exposure to vasopressors and a 90-day mortality rate similar to the comparison group. The SSC recommendation for a target MAP of 65 mmHg reflects the lack of advantage associated with higher MAP targets and the lack of harm among elderly patients with lower MAP targets of 60 mmHg to 65 mmHg (Evans et al. 2021, 1).

In summary, the SSC recommends, as a best practice statement, the immediate treatment and resuscitation of adults with sepsis and septic shock, to include: (Evans et al. 2021, 1).

- Using crystalloids as first-line fluid for resuscitation (strong recommendation), with a suggestion to use balanced crystalloid instead of normal saline, a suggestion against the use of gelatin and a recommendation against the use of starches for resuscitation.

- Administering at least 30 ml/kg of crystalloid fluid within the first 3 hours of resuscitation for sepsis-induced hypoperfusion or septic shock (weak recommendation).

- Guiding resuscitation to decrease serum lactate in patients with elevated lactate levels over not using serum lactate (weak recommendation).

- Using dynamic measures to guide fluid resuscitation (i.e., response to passive leg raise or a fluid bolus; stroke volume, stroke volume variation, pulse pressure variation or echocardiography) over physical examination or static parameters alone (weak recommendation).

- Using capillary refill time to guide resuscitation as an adjunct to other measures of perfusion (weak recommendation).

- Using an initial target MAP of 65 mmHg over higher MAP targets in the initial resuscitation of adults with septic shock requiring vasopressors (strong recommendation).

Insights and Implications

The SSC guidelines for the initial resuscitation of a patient with sepsis and septic shock are unchanged from 2016, except for the addition of a best practice statement recommendation that treatment and resuscitation for sepsis and septic shock begin immediately, and a downgrading of evidence from strong to weak for the administration of crystalloid fluids, at least 30 ml/kg within the first 3 hours of resuscitation.

Timing of Antimicrobial Administration for Sepsis and Septic Shock

Last Full Review: Surviving Sepsis Campaign 2021

Antibiotics are critical for reducing the mortality from sepsis and septic shock. Previous recommendations from the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) advised starting antibiotics as soon as possible after recognition of sepsis and septic shock, and within 1 hour for both. For 2021, the SSC strongly recommends that for adults with possible septic shock or a high likelihood for sepsis, antimicrobials be administered immediately, ideally within 1 hour of recognition. What evidence supports this change?

Red Cross Guidelines

- For adults with a high likelihood of sepsis, with or without shock, antimicrobials should be administered immediately, ideally within 1 hour of recognition of septic shock.

- For adults with shock and possible sepsis, antimicrobials should be administered immediately, ideally within 1 hour of recognition.

- For adults with possible sepsis without shock, it is reasonable to rapidly evaluate the patient and if concern for infection persists, administer antimicrobials within 3 hours from the time when sepsis was first recognized.

- For adults with sepsis or septic shock who are at high risk for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), empiric antimicrobials with coverage for MRSA should be initiated.

- For adults with sepsis or septic shock who are at low risk for MRSA, it is reasonable to not include empiric antimicrobial coverage for MRSA.

- For adults with sepsis or septic shock who are at high risk of multidrug resistant (MDR) organisms, use two antimicrobials with gram-negative coverage for empiric treatment.

- For adults with sepsis or septic shock who are at low risk of MDR organisms, use one gram-negative antimicrobial for empiric treatment.

Evidence Summary

Several large studies (Seymour et al. 2017, 2235; Liu et al. 2017, 856; Peltan et al. 2019, 938) have reported a strong association between each hour delay in time from emergency department arrival to the administration of antimicrobials and in-hospital mortality with septic shock, while other observational studies at risk of bias and with design limitations have not observed an association between timing of antimicrobial administration and mortality (Evans et al. 2021, 1). For sepsis without shock, the association between time to antimicrobial administration and mortality is inconsistent but suggests an increase in mortality with interval times to antimicrobial administration exceeding 3 to 5 hours from hospital arrival and/or sepsis recognition. Thus, for adults with possible sepsis without shock, a time-limited course of rapid investigation is suggested, and if concern for infection persists, antimicrobials should be administered within 3 hours from the time when sepsis was first recognized (Evans et al. 2021, 1).

Outcomes from studies of antibiotic coverage for documented methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection vary, with some showing that delays of greater than 24 to 48 hours to antibiotic administration being associated with increased mortality, and other studies not finding this association. The use of broad-spectrum antibiotics against MRSA in undifferentiated patients with pneumonia or sepsis has been shown to be associated with higher mortality (Evans et al. 2021, 1). The decision for use of antimicrobials active against MRSA depends on the likelihood of MRSA causing an infection, the risk of harm from withholding treatment when a patient has MRSA and the risk of harm from MRSA treatment when MRSA is absent. When adults with sepsis or septic shock are at high risk of MRSA, it is recommended to use empiric antimicrobials with MRSA coverage, while, conversely, it is suggested against using empiric antimicrobials with MRSA coverage for those at low risk of MRSA.

Insights and Implications

In summary, when sepsis is definite or probable and regardless of the presence or absence of shock, antimicrobials should be administered immediately and ideally within 1 hour of recognition. In a patient with shock and possible sepsis, antimicrobials should also be administered immediately and ideally within 1 hour of recognition. If sepsis is possible and shock is absent, then the patient should be rapidly assessed for an infectious versus a noninfectious cause of acute illness, including obtaining a history and physical examination, testing for infectious and noninfectious causes of acute illness, and treating acute conditions that can mimic sepsis. Ideally, assessment should be completed within 3 hours of presentation and antimicrobials should be administered within that time if the likelihood of infection is thought to be high.

Vasoactive Agents for Adults with Septic Shock

Last Full Review: Surviving Sepsis Campaign 2021

Patients with septic shock who do not respond to fluid resuscitation will require support with vasopressors. Is there scientific evidence to support the choice of one initial vasopressor over another? What alternatives or additional vasopressors should be considered? Should other vasopressors be selected for patients with septic shock and cardiac dysfunction?

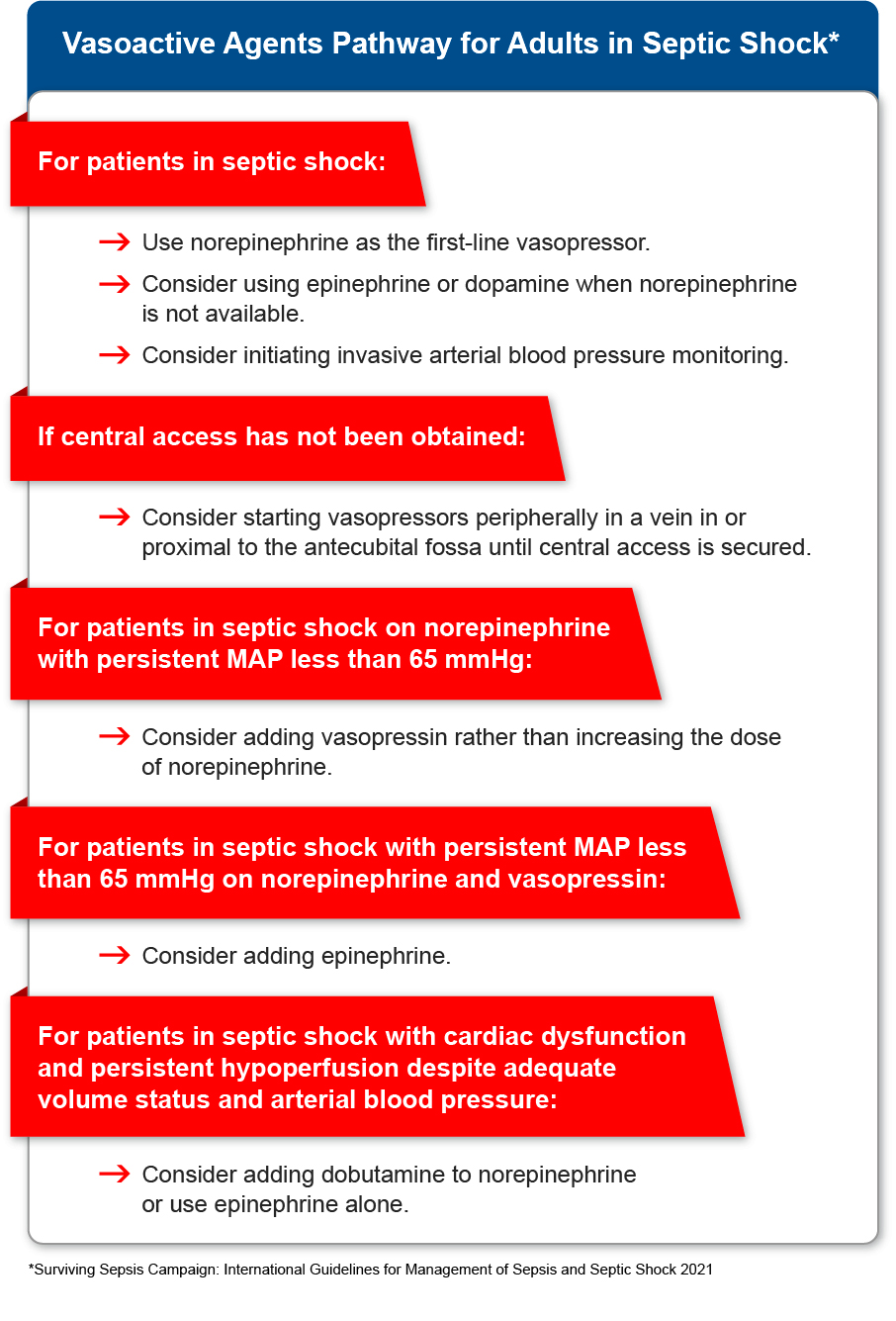

Red Cross Guidelines

- Adults with septic shock should have vasopressors begun through peripheral access to improve mean arterial pressure (MAP) rather than waiting for central access.

- Norepinephrine should be used as the first-line vasopressor agent in adults with septic shock unresponsive to intravenous fluid resuscitation.

- Adults with septic shock should be treated initially with norepinephrine over other vasopressors.

- It is reasonable to use epinephrine or dopamine for adults with septic shock when norepinephrine is not available.

- For adults with septic shock and persistent MAP less than 65 millimeters of mercury (mmHg) on norepinephrine, consider adding vasopressin rather than increasing the dose of norepinephrine.

- For adults with septic shock and persistent MAP less than 65 mmHg on norepinephrine and vasopressin, consider adding epinephrine.

- For adults with septic shock and cardiac dysfunction, add dobutamine to norepinephrine or use epinephrine alone.

- For adults with septic shock, consider invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring as soon as practical and if resources are available.

Evidence Summary

Norepinephrine is an alpha-1 and beta-1 adrenergic receptor agonist with more potent vasoconstrictor effects than dopamine, resulting in increased mean arterial pressure (MAP) without a significant effect on heart rate. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in a 2000 systematic review showed a lower mortality (RR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.81–0.98) and risk of arrhythmia (RR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.40–0.58) with the use of norepinephrine compared with dopamine (Avni et al. 2015, e0129305).

Epinephrine at higher doses produces increased cardiac output and systematic vascular resistance, but its use may be limited by adverse effects, such as arrhythmias and splanchnic ischemia, and it may increase lactate production. Despite these challenges, a recent RCT found no difference in 90-day mortality and vasopressor-free days with epinephrine use in patients with shock compared with norepinephrine (Myburgh et al. 2008, 2226).

Vasopressin, an endogenous peptide hormone, produces vasoconstrictor effects from multiple mechanisms. A fixed dose of 0.03 units per minute is typically used for septic shock; higher doses may be associated with adverse effects, such as cardiac ischemia. Previous studies have shown improved survival for a subgroup of patients with less severe shock who received norepinephrine plus vasopressin (Russell et al. 2008, 877) and a catecholamine-sparing effect from vasopressin (Russell et al. 2008, 877; Ukor and Walley. 2019, 247).

A systematic review of 10 RCTs by the SSC showed reduced mortality with the use of vasopressin with norepinephrine as compared with norepinephrine alone (RR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.83–0.99) and no difference in risks of digital ischemia or arrhythmias (Evans et al. 2021, 1).

A new weak recommendation from the SSC suggests that for adults with septic shock, vasopressors should be started by peripheral intravenous access to restore MAP rather than delaying initiation until a central venous access is secured. The SSC guidelines otherwise remain essentially unchanged for the hemodynamic management of adults with septic shock using vasoactive agents, with a strong recommendation to use norepinephrine as the first-line agent.

Alternatives to norepinephrine, if not available, include epinephrine or dopamine. If the MAP levels remain inadequate despite norepinephrine, it is suggested to add vasopressin rather than escalating the dose of norepinephrine. If the MAP levels remain inadequate despite norepinephrine and vasopressin, it is suggested to add epinephrine. For septic shock and cardiac dysfunction with persistent hypoperfusion despite adequate volume status and arterial blood pressure, the SSC suggests adding either dobutamine to norepinephrine or using epinephrine alone, while a new weak recommendation suggests against using levosimendan (Evans et al. 2021, 1).

Insights and Implications

The desirable and undesirable or potential harm from vasopressors were considered by the SSC in making the recommendation to use norepinephrine rather than dopamine, vasopressin, epinephrine and other vasopressors as a first-line agent for septic shock. Additional considerations were the higher cost of vasopressin and limited availability. In summary, norepinephrine should be used as a first-line vasopressor. If not available, epinephrine and dopamine remain alternative vasopressors. A MAP of 65 mmHg should be targeted for patients with septic shock receiving vasopressors. Healthcare professionals may consider initiating invasive monitoring of arterial blood pressure monitoring, and if central access has not been obtained, consider starting vasopressors peripherally. Should MAP targets not be met despite low-to-moderate dose norepinephrine, healthcare professionals may consider adding vasopressin. The usual dose range for norepinephrine is 0.25 to 0.5 micrograms per kilogram per minute. If the MAP remains inadequate, healthcare professionals may consider adding epinephrine.

Oxygenation and Ventilatory Management of Sepsis with Respiratory Failure

Last Full Review: Surviving Sepsis Campaign 2021

What oxygenation and ventilatory management strategy is recommended for patients with sepsis-induced hypoxemic respiratory failure, with or without acute respiratory distress syndrome?

Red Cross Guidelines

- For adults with sepsis-induced hypoxemic respiratory failure, it is reasonable to use high-flow nasal oxygen, when tolerated. Consider the use of noninvasive ventilation based on clinical judgment.

- For mechanically ventilated adults with sepsis-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and for sepsis-induced respiratory failure without ARDS, use a low-tidal volume strategy over a high-tidal volume strategy.

- For mechanically ventilated adults with sepsis-induced severe ARDS, target an upper limit goal of 30 millimeters of mercury for plateau pressure.

- For adults with moderate to severe sepsis-induced ARDS, use a prone position for greater than 12 hours per day.

Evidence Summary

Sepsis with pneumonia or other infections can cause acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. In the absence of hypercapnia, hypoxia is managed initially with high-concentration oxygen through a nasal cannula, face mask or Venturi mask. As hypoxia worsens, noninvasive ventilation or high-flow oxygen may improve gas exchange and help reduce the work of breathing, avoiding potential complications of intubation and mechanical ventilation. Highflow nasal cannula therapy allows for airflows up to 60 liters per minute (fraction of inspired oxygen, 95% to 100%) but is less effective than noninvasive ventilation at reducing the work of breathing and providing greater positive end-expiratory pressure (Mauri et al. 2017, 1207).

One large randomized controlled trial evaluated ventilation strategies for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure despite the use of conventional oxygen (Frat et al. 2015, 2185). For a strategy of noninvasive ventilation compared with high-flow nasal cannula therapy, no difference in intubation rate at 28 days was reported but improved 90-day survival was reported with the use of high-flow nasal cannula compared with noninvasive ventilation (OR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.2–0.85). Analysis of patients with severe hypoxemia reported a 35 percent intubation rate with high-flow nasal cannula therapy compared with noninvasive ventilation (58 percent).

A new recommendation from the SSC suggests the use of high-flow nasal oxygen over noninvasive ventilation for adults with sepsis-induced hypoxemic respiratory failure. There was insufficient evidence to make a recommendation on the use of conservative oxygen targets. Unchanged strong recommendations include using a low-tidal volume ventilation strategy (6 ml/kg) over a high-tidal volume strategy (less than 10 ml/kg) for adults with sepsis-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and an upper limit goal for plateau pressures of 30 centimeters water, and in those with moderate to severe ARDS using prone ventilation for greater than 12 hours a day. For sepsis-induced respiratory failure without ARDS, a low-tidal volume is suggested compared with high-tidal volume ventilation (Evans et al. 2021, 1).

Insights and Implications

While high-flow nasal cannula therapy appears to be beneficial for sepsis patients with progressive hypoxia without hypercapnia, these patients are at high risk of needing intubation and require close monitoring for ventilatory failure. There was insufficient evidence to make a recommendation on the use of conservative oxygen targets in adults with sepsis-induced hypoxemic respiratory failure, but several trials are currently underway. Similarly, there was insufficient evidence to make a recommendation on the use of noninvasive ventilation compared with invasive ventilation for adults with sepsis-induced hypoxemic respiratory failure.